Developers and heritage enthusiasts united on adaptive reuse of old buildings

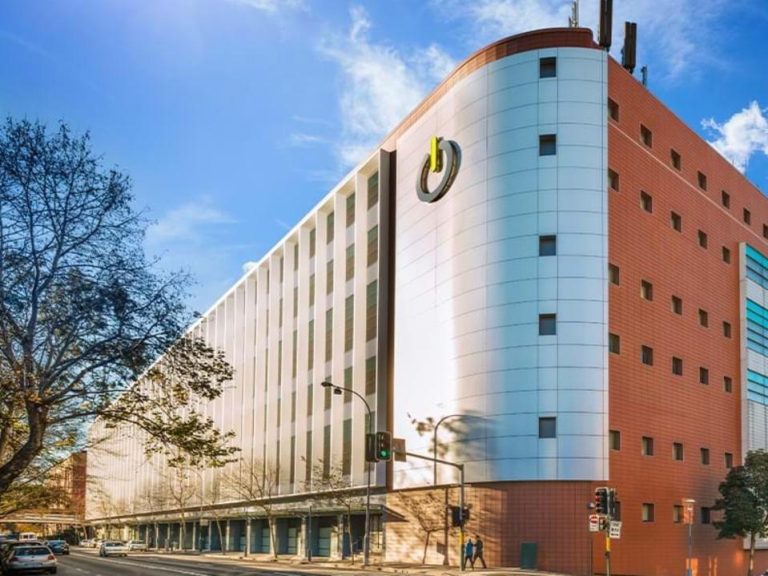

Gray Puksand’s $90m repurposing of the old Melford Motors showroom on 611 Elizabeth Street, Melbourne, for PDG.

Property developers and heritage consultants have united on a decades-old commercial property trend that is beginning to resurface, one that experts say might just encourage workers to return to the CBD.

That shared goal exists within the redevelopment of old buildings that have outlived their purpose, and turning them into modern offices, schools and health precincts.

Adaptive reuse – the term given to repurposing a building for other means – has again shot to fame in recent months, despite the building style existing back as far as the 1970s, says Deakin University cultural heritage lecturer James Lesh.

“Adaptive reuse isn’t new. It’s something that we’ve been doing in Australia since the late 1970s,” Dr Lesh said.

“However, adaptive reuse is increasingly celebrated by the development community and also by the heritage and design community.

“We’re seeing tremendous CBD development pressures, with every parcel of developable land a potential investment opportunity,” he said. “Heritage properties also become opportunities when they’re not adequately performing from a development and design perspective.”

Across Victoria this year alone, developer Gray Puksand will complete 22 adaptive reuse projects worth more than $500m. Across Australia, that number and value rises again.

Gray Puksand partner Kelly Wellington said adaptive reuse projects now make up about 15 per cent of the firm’s work.

611 Elizabeth Street.

Asked what the main difference was between minor renovations and adaptive reuse, Ms Wellington said it was about repurposing.

“Adaptive reuse is where you’ve got an existing building that has outlived its current or intended use,” she said.

“Rather than just trying to pull down buildings, we can convert them. Quite often they have attributes like old timber floors that newer buildings perhaps don’t have, and we can convert them into amazing spaces.”

Gray Puksand’s recently completed adaptive reuse projects include 611 Elizabeth St in Melbourne for PDG, and Yarra Falls, Abbotsford, for Abacus Property Group.

PDG paid $90m to transform the old Melford Motors showroom on 611 Elizabeth St into a 20,000sq m space with a six-level tower overhead, modern interior and basement levels added.

Yarra Falls was transformed into a multi-use city fringe office with about 8000sq m of commercial office space, 8500sq m of flexible space and an on-site gym and garden.

The firm’s upcoming Victoria projects including 300 Flinders St in the Melbourne CBD.

Gray Puksand’s redevelopment of Yarra Falls transformed the building into a multi-use city fringe office with about 8000sq m of commercial office space, 8500sq m of flexible space and an on-site gym and garden.

Gray Puksand will reposition 12,000sq m of office space, formerly used by Victoria University, for Futuro Capital & Maprop. The building will also have its foyer redeveloped into a space that links Flinders Lane and Flinders St via Mill Place.

Another building about to be repurposed is APPF and Lend Lease’s 469 Latrobe St. The building is having its edges transformed to work with laneway frontages and will be connected to adjacent building 485 Latrobe St, also owned by APPF and Lendlease.

Ms Wellington said a new interest in adaptive reuse appears to be inspired from lockdowns and businesses shedding their office space.

“The idea that you can reuse an existing building has been around for some time, but it’s probably being considered more due to the position people have in not having tenants,” she said.

Australian workers with the ability to work from home have become used to the added comforts, Ms Wellington said.

“I think just generally people have had the ability to be at home, have had the ability to go and enjoy the comforts of home while working, so I think it’s really important that commercial workspaces need to provide something more than they used to,” she said.

Dr Lesh said limited developable land had spurred developers to reconsider adaptive use more creatively.

As employers struggle to bring their staff back to work, Dr Lesh said it was possible that older buildings turned into offices might provide the push needed.

“Heritage redevelopment, when done in a genuine and sophisticated way, based on an understanding of fabric and history, provides authenticity and texture to places, which means tenants and communities love them,” he said.

Deakin University cultural heritage lecturer Dr James Lesh.

Heritage 21 director Paul Rappoport.

Heritage 21 director Paul Rappoport agrees.

“With all heritage buildings, there’s a sense of mystery, a sense of nostalgia, a sense of finding some kind of affirmation in the past … possibly due to fear about the future or the unknown,” he said. “It’s a very difficult thing to define but people generally do enjoy heritage in a subconscious fashion.”

Mr Rappoport said councils were aware of the general interest in heritage buildings and sites, and some capitalised on this to the detriment of the sites.

“The planners and the people who run the city notice that there is a lot of tourism associated with heritage,” he said. “That’s been pumped out with Mykonos, Greece, for the past 40 years. In some case its overdone, like Venice, Italy. There you get 10-storey cruise ships going up the Grand Canal.”

Ms Wellington said while adaptive reuse was often associated with older and heritage buildings, there was a lot developers could be doing now to ensure new buildings could be repurposed in future. One example, she said, existed within car parks in commercial offices.

Gray Puksand’s redevelopment of Yarra Falls in Melbourne.

“The standard height of a car park is much lower than an office floor, so by expanding that you allow for future transformation, especially as we shift towards car-less CBDs,” she said.

Mr Rappoport sees commercial towers being transformed into residential spaces as the next big trend to land in Australian cities.

“A lot of the offices which have almost been abandoned lend themselves very well to become residential. People do like adaptive reuse and if it’s done cleverly it enhances that (fondness) even more,” he said.

“We go through cycles in terms of recycling heritage buildings. There was a lot of adaptive reuse in the ’90s of old warehouses into residential apartments all through Surry Hills (in Sydney) and through to the city. It goes in waves and it depends on policy and legislation.”