Ghost developments: Australia’s tourism meccas that are no more (or never were)

From glittering island casinos to sun-dappled water parks, many of Australia’s former tourist meccas now sit abandoned as mere shells of their once glory days.

While some of these once thriving holiday destinations have been earmarked for redevelopment, others lie in wait as nature eats them up.

Atlantis Marine Park, Two Rocks

It was once a symbol of Western Australia’s 1980s tourism boom, but today the only remains left of Atlantis Marine Park are old Roman sculptures, including a 10-metre tall statue of King Neptune.

A partnership between Alan Bond and Japan-based Tokyu Corporation, the theme park was originally planned as part of the ambitious Yanchep Sun City project – a sprawling holiday destination and satellite city.

Visitors can still see the King Neptune sculpture at the site of the former Atlantis Marine Park. Picture: Facebook

The park boasted water slides, aqua playgrounds, roller coasters, paddle boats, seal shows and seven wild bottlenose dolphins, who were captured and trained to perform in live shows.

In the midst of low profits and dwindling cash flow, the Tokyu Corporation was forced to close the park in 1990.

In 2015, volunteers refurbished the King Neptune sculpture and reopened the area to visitors, who can now wander around the site and imagine how it once was.

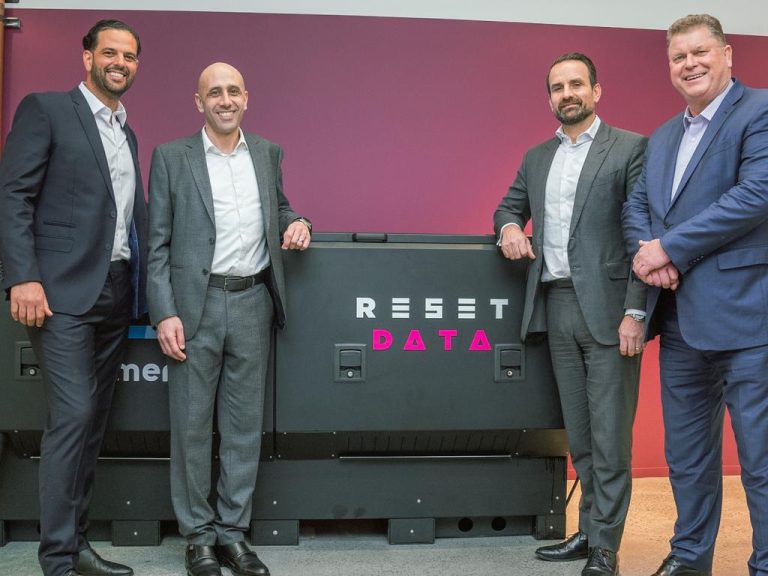

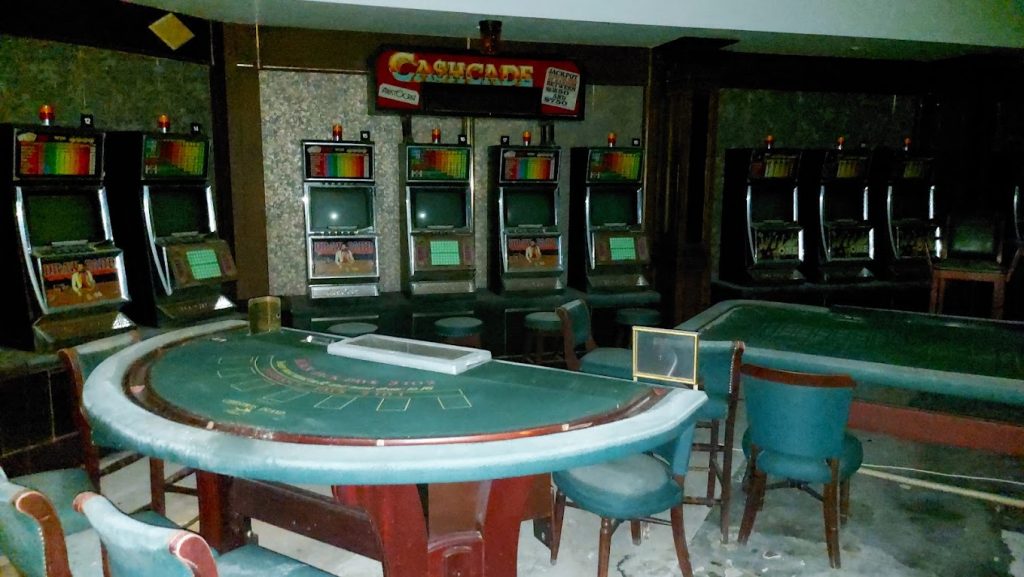

The Christmas Island Casino and Resort

Before it became the infamous site of an immigration detention centre, Christmas Island was once home to the most profitable casino in the world, generating more than $5 billion a year during the 1990s.

With Jakarta only an hour’s flight away, The Christmas Island Casino and Resort was the playground of Indonesia’s high rolling gambling elite.

The Christmas Island Casino and Resort closed in 1998 due to the Asian financial crisis. Picture: Fredo Frog

According to local resident Peter Griggs, who helped set up the operation, the casino had 156 guest rooms, several restaurants, nightclubs and a swimming pool – all manned by 400 full-time staff.

During its brief but highly lucrative four-year run, the island’s population grew from 800 to 2,700.

In 1998, the casino closed due to the Asian financial crisis.

Today, the Christmas Island Casino and Resort site is one of a number of abandoned buildings dotted around the tiny remote isle.

Dismal Swamp, Tasmania

Famous for the largest sinkhole in the southern hemisphere, Dismal Swamp was once a popular tourist attraction near Togari in Tasmania’s north-west.

Developed by Forestry Tasmania and first opened in 2004, the $4 million site featured a maze, boardwalks, sculptures and artworks from local artists, plus an impressive 110-metre slide snaking through the forest.

The attraction had hopes of driving tourists to the remote corner of the state, but after years of operational troubles, Dismal Swamp shut its doors in 2019.

The Dismal Swamp opened in Tasmania’s north-west in 2004. Picture: Richard Bennett

The site has been left in a state of disrepair and decay ever since, with many of the art installations vandalised or crushed by falling trees.

Circular Head Tourism Association holds a grand vision to revamp Dismal Swamp into an adventure hub that will include an obstacle course, educational cinema, eateries and accommodation.

In 2022, the Labor government committed $12.5 million to get the project ready for private investment. According to reports, the promised funds are still yet to be released.

HTL Property’s James Smithers said slower economic growth and budgetary pressures are expected to continue to impact the renewal of projects like these over the next 24 months.

“We have seen many leisure assets fall into despair in recent years with a combination of weather events, operating costs and a shift in consumer behaviour reducing the viability of the sector and restoration of these assets.”

Aquis Casino, Yorkeys Knob

While the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s were marked by grand tourism meccas falling by the wayside, the more recent past has seen tourism developments failing to get off the ground.

Many of these unsuccessful projects were earmarked for construction in the sun-drenched holiday mecca of Cairns.

The Aquis Casino and Resort plans were shelved in 2016. Picture: Realcommercial.com.au

The ambitious $8.1 billion Aquis Casino and resort in Yorkeys Knob was announced in 2013 by Hong Kong billionaire and Aquis chairman Tony Fung.

At the time, it was gearing up to be the world’s biggest six-star hotel and casino with 7,500 hotel rooms, an 18-hole golf course and lagoon complex.

However, by 2016, Aquis had run into trouble securing a casino licence and quickly dropped plans to build the casino.

Adventure Waters Theme Park, Barron

In 2009, the much-hyped Adventure Waters Theme Park was approved by Cairns council and was being spearheaded by Cairns developer Paul Freebody.

The $45 million waterpark, located 10km north of Cairns CBD, was to feature some of the most white-knuckle rides in the industry, including an action river and wave rider, children’s water-play areas, function rooms, restaurant precinct and retail areas.

An artist’s impression of the proposed Adventure Waters Theme Park in Cairns. Picture: Queensland Government

At the time, Mr Freebody boasted the park could attract up to 300,000 visitors a year to the region, but construction for the leisure project never got off the ground.

Many tourism developers continue to face difficulties in transitioning from the DA approval stage to the building phase due to rising costs in construction, said Mr Smithers.

“The upward trajectory of construction spending itself can be attributed to many factors including inflationary pressures, rising cost of capital, increased constraints on banks, labour costs and shortages, rising insurance rates and material costs,” he explained.

“These increases have eroded investor returns and developers have also become fatigued. Many have mothballed projects, pivoted to different strategies, or are attempting to wait for market conditions to normalise.”

As of last month, the 6.98-hectare Adventure Waters Theme Park site is back on the market.