Probuild problems echo a building industry in crisis

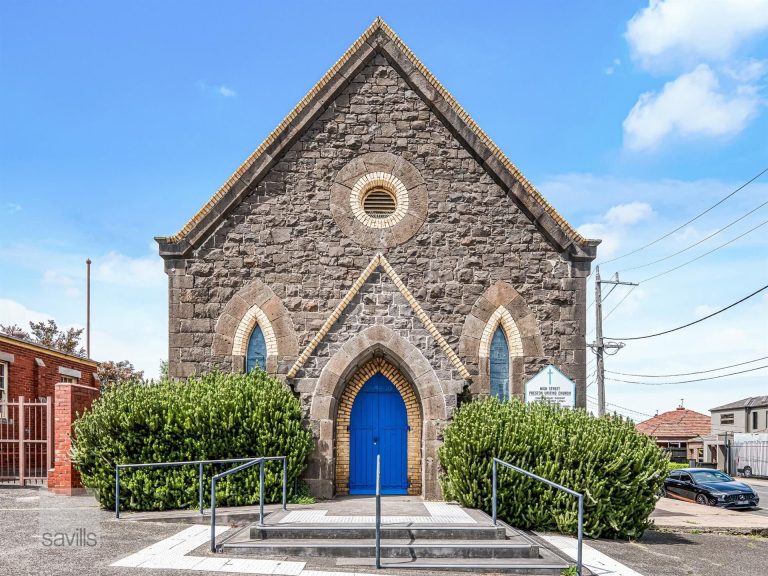

Probuild’s 18 projects span the country, including high-rise towers for big name developers and infrastructure such as roads. Picture: David Caird

The collapse of construction company Probuild has revealed deep-seated problems in the building and infrastructure industry, sparking calls for urgent reforms to prevent more failures.

The litany of problems is well known: razor-thin margins, supply chain breakdowns, unexpectedly higher costs, inflexible contracts, pandemic-related shortages and inefficiencies, union concerns and lumpy cashflows.

They all played a part in the once proud builder’s demise and others are under threat.

Probuild’s 18 projects span the country, including high-rise towers for big name developers and infrastructure such as roads.

The company came to grief in both fields ahead of its dramatic collapse when South African parent, construction giant Wilson Bayly Holmes-Ovcon, pulled its financial support.

The collapse has been a long time coming and followed other firms hitting the wall, notably Brisbane-based home builder Privium and Melbourne-based ABD.

Construction makes up about a quarter of the insolvencies across Australia.

Builders are facing the same cocktail of pressures, along with new problems in securing finance and blowouts on projects that have left both subcontractors and tradies short.

Administrator Deloitte insist it will be able to quickly resurrect and sell off the Probuild empire, and complete iconic jobs like The Ribbon in Sydney’s Darling Harbour, Melbourne apartment towers and hotels and the CSL headquarters.

But it may not be so simple, as major rivals target both the entire entity and key jobs. Already industry giants Multiplex and Roberts Co have separately been linked to Victorian projects.

Taking on the Probuild contracts may be tough as the firm ran aground partly due to underquoting, which failed to account for key risks.

Developers may also look to protect their own interests and seek out new builders without the complications of a collapsed group.

Among Probuild’s projects is a $1bn accommodation and entertainment complex designed by Hassell on the eastern edge of Darling Harbour in Sydney. Picture: John Feder

The picture will become clearer at a creditors’ meeting on Friday but until then the thousands of workers, subcontractors and buyers affected by the collapse are in the dark, concerned they will be left out of pocket.

Behind the heat from angry subcontractors, Probuild is hoping that governments could inject funds to help it complete major projects that are vital for recharging city economies, particularly CBD apartment and hotel towers.

Probuild’s scale, with an estimated $5bn of projects under way, makes it a standout, but its issues came as little surprise, given the lopsided structures that are hampering builders.

One consultant said that many builders were victims of the race to the bottom, which was passed down through the whole industry chain, including subbies, suppliers and consultants. “The lowest-price strategy does not work; it becomes a race to the bottom of the ocean,” another warned.

Risk Engineering Society president Pedram Danesh-Mand argues the system is not broken. But he says builders need well-defined governance, delivery strategies, and portfolio controls and assurance, as well as technical capabilities and the right contract arrangements.

Policymakers are also alive to the challenge. Infrastructure Australia’s chief of policy and research Peter Colacino says Probuild’s administration is a sign of the current fragility of the Australian construction and infrastructure sectors. “It is important the infrastructure sector looks to reform to improve infrastructure industry productivity and support innovation,” he says.

Peak bodies representing large contractors are working on new structures which align the interests of builders and developers rather than them being caught up in thinking construction is a “zero sum game”, says Australian Constructors Association chief executive Jon Davies.

He’s pushing for new ratings to improve transparency on large projects rather than simply relying on regulations hitting the already hard-pressed sector. Davies says the construction industry is not in good shape, with insolvencies on the rise and workforce shortages expected to peak in less than 18 months.

Skilled migration and training are expected to provide some relief for the skills shortage, but only a major industry shake-up targeting productivity will fully solve the problem, he says.

Davies is worried that contractors are being asked to lock in prices for uncontrollable risks like material price jumps and pandemic risk pushing back long-dated projects.

“It is time for government and ethical investors to lead the way in creating a more sustainable and productive industry,” he says.

He says the federal government, which bankrolls major projects, could shake up the industry by implementing a “Future Australian Infrastructure Rating” system.

A FAIR scheme would see government-funded projects rated on how well they performed against reform areas such as improved productivity and increased innovation.

“FAIR has the potential to address the industry’s challenges, including the critical skills shortage, while unlocking productivity gains in the vicinity of $15bn annually,” he says.

“Ultimately, the FAIR scheme could also be used by ethical investors such as super funds to demonstrate their own support and action for improved industry outcomes,” Davies says.

With a new approach on the table, the time for passing the buck may have passed.