Why US-style rent controls are not the answer to Australia’s housing crunch

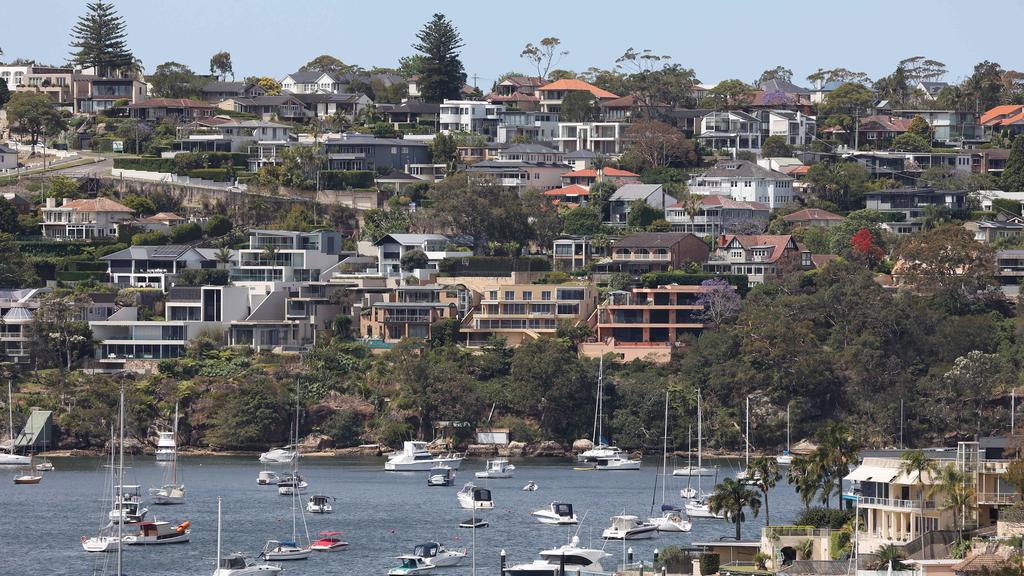

The biggest objection to rent controls is that they reduce the supply of rentals and ultimately make renting harder and more expensive. Picture: NCA NewsWire / David Swift

Rental markets around the country are extremely tight, with vacancy rates nationally sitting at less than 1.5 per cent – but calls for price controls won’t solve the problem.

There are many reasons why markets are so challenged, including more renters living alone since the pandemic, investors selling out, and more recently, the return of migration.

The result is that rent prices are growing very quickly. Over the year to March 2023, median advertised rents on realestate.com.au rose by 11.1 per cent, with some areas seeing even faster growth.

Clearly, that’s putting pressure on the budgets of many tenants, in an environment in which cost-of-living pressures are already rising. As a result, there have been calls for governments to intervene.

One solution that has been widely suggested is rent control, although it is yet to be picked up by governments.

NSW Premier Chris Minns this month ruled out rent caps as a solution to fix the state’s rental crisis, while Queensland‘s Palaszczuk government last week passed laws to limit rent increases to once a year.

Strict controls can hold down the cost of rents for some but they create a host of detrimental side effects.

In particular, rent controls can end up making renting more expensive for other tenants who don’t benefit from the policy. They can reduce the supply of rentals, making it harder to find a rental, as well as lead to renters staying in homes that aren’t appropriate for their needs. And there’s the likelihood they could lead to lower-quality and worse-maintained rental stock.

The term “rent controls” can cover a broad range of restrictions on tenant-landlord relations. But the types of rent controls I want to look at here are those that restrict the prices of rents in some way.

These controls are classified into two broad categories. Rent freezes, or hard controls, cap the level of rents. And rent stabilisation, or soft controls, are policies that limit how quickly rents can increase for occupied properties, rather than capping or freezing the level of rents.

Often, rents are uncapped between tenancies, for example, once the property becomes vacant, the landlord can advertise any rent they like for the incoming tenant.

Australia has some experience with rent control. Rent controls were introduced during World War II by the government, with controls ending in 1948. Since then, rent controls have been rare in Australia.

The rental crisis, which has resulted in protests, would not be adequately addressed by implementing rent controls. Picture: Getty Images

The key counter examples are NSW and the ACT. NSW persisted with the rent caps that were in place during World War II. Rent control in NSW largely ended in the 1960s. The ACT introduced rent control in 1974; this was abolished two years later.

Do rent controls achieve their stated goal? Do they make rents cheaper? The short answer is: for some people, yes.

Most studies find that rent controls create cheaper rents for the incumbent renters that benefit from the controls.

And these discounts can be significant. By the time NSW lifted rent controls, controlled rents were around 50 per cent to 60 per cent cheaper than market rents. As another example, a study found that Massachusetts’ rent caps lowered rents for controlled apartments by about one-fifth.

But rent controls create spillovers that raise rents in the non-controlled part of the rental market – eligible tenants get lower rents, but other renters end up paying more.

Rent stabilisation can also have an unfortunate side effect. Landlords have incentives to choose less-secure tenants because shorter tenures give landlords more opportunities to adjust rents when the property is vacant. That can make renting harder for the types of renters that particularly value stability like families and older households. Unfortunately, rent control comes at a significant cost, including to the groups it purports to help.

Studies have examined many different effects, but I’ll focus on three: reduced supply of rental housing; renters staying in homes that aren’t appropriate for their needs; and poor maintenance and lower quality rental dwellings.

The biggest objection to rent controls is that they reduce the supply of rentals and ultimately make renting harder and more expensive.

This happens through two avenues: encouraging landlords to move properties out of the rental market, and undermining the incentive to build new rentals.

The first avenue is very clear in the evidence: rent controls clearly lead to properties being removed from the rental market. And that’s true even of softer, rent stabilisation policies, not just for rent caps.

PropTrack economist Angus Moore

A compelling study of San Francisco’s rent stabilisation policy, which capped annual rent increases for eligible properties to no more than 7 per cent, found there was a 15 per cent decrease in rent-controlled properties because landlords redeveloped or sold rental housing to owner occupiers.

One of the key outcomes from rent control was stock being redeveloped into higher-end housing: rent control contributed to gentrification.

The US study found that high-end housing, developed in response to rent control, attracted residents with at least 18 per cent higher income, relative to non-rent-controlled buildings.

Another US study on rent control in Massachusetts, found that units were six percentage points more likely to become rentals after rent control ended than before – meaning thousands of units were kept out of the rental market by rent control.

The second avenue is straight forward in theory; controlled rents mean a lower return from building new rentals, so fewer get built.

In practice, there’s surprisingly little evidence on the impact of rent controls on construction for a simple reason: most rent controls specifically exempt new construction precisely because policymakers are concerned about this effect.

As a result the evidence on this effect is weak. But it has been found to have either no effect or a negative effect.

Rent controls also lead to poor matching between what renters need and where they live. Housing, by nature, is a limited and scarce resource – so ensuring that people are in homes that suit their needs is important.

With rent freezes and caps, where rents are far below their market rate, rentals essentially become a lottery providing a windfall to the household lucky enough to be living there. This flattening of rents can lead to households staying in homes that they value very little, which others would value far more.

But because the rent doesn’t reflect that value others place on the home, there is no incentive for the incumbent household to move.

Empirically, this is what we see in tightly rent controlled markets. The seminal paper on this issue compared similar demographic cohorts and the dwellings they live in across cities with and without rent control.

It found that, because of rent control, 21 per cent of New York renters live in apartments that are too big or too small – and this was not driven by the fact New York is more expensive to rent in than other cities.

A study of rent control in Massachusetts found that its repeal led to a significant improvement in aesthetic maintenance – chipped paint, holes in the walls and floors, and loose railings.

While enforcement mechanisms can help mitigate the incentives to under-invest, these mechanisms are imperfect and the result is that small maintenance items get ignored.

If rent controls are, at best, an imperfect way to help renters, what else can we do?

In the short-term, a less distortionary way to help renters would be to raise Commonwealth Rent Assistance. Rent assistance is better targeted at those that need it. It has fewer negative side effects; and it is not, contrary to some counter arguments, a subsidy to landlords.

Studies of Australia’s rent assistance find it raises rents only modestly, meaning the payment almost entirely benefits the renter.

But longer-term, the solution to rental affordability is about building enough homes.

Rents are growing quickly right now because rental homes are very scarce – building more would solve that.

Angus Moore is an economist at PropTrack